ST. LOUIS • To call the big empty house in the 4500 block of Labadie Avenue an eyesore would be kind.

Its yard is an explosion of hip-high grass. Loose bricks perch on the front porch roof. The upstairs windows are long gone and through one, sunlight shines where a ceiling should be.

The Labadie house, located in the Greater Ville neighborhood of north St. Louis, has a list of code violations and Building Division fines, all ignored. No one has paid taxes on the property since at least 2009. Records say it is owned by a mysterious holding company named Urban Assets LLC, , according to city real estate records. The ownership of Urban Assets, however, is not a matter of public record.

Rotting vacant buildings and scofflaw speculators are nothing new on the city’s north side, where decades of population loss have left some blocks more than half-empty and thousands of once-grand brick homes to rot. But city officials and neighborhood activists say they’ve never seen anything like Urban Assets, which bought up property in a flurry in 2008 and 2009, made no improvements and left tax bills unpaid and court summonses unanswered. Now this summer, their properties have started to hit the auction block for the unpaid taxes, but buyers are few, and most appear bound for the city’s already-swollen bank of property no one wants.

People are also reading…

“They’re completely unaccountable,” said Michael Allen, a preservationist and blogger who has researched Urban Assets. “They’re not meeting any of their legal obligations and they’re just degrading (city) blocks.”

The only name associated with Urban Assets is that of Harvey Noble, a veteran real estate broker who’s listed on Missouri secretary of state filings as the limited liability company’s registered agent, and who signs its property deeds. Noble, who is in his early 80s, has been a player in city real estate for decades and has long worked as a frontman for people who want to buy property but keep their identity hidden. It was Noble who formed the shell companies developer Paul McKee used to amass hundreds of pieces of ground in north St. Louis for his NorthSide Regeneration project. And he has performed similar work for a variety of other smaller efforts.

At the same time, Noble and his longtime business partner Steve Goldman have worked for a variety of city-run development agencies. Just since 2008, their firm Eagle Realty has been paid nearly $450,000 to appraise property for the Land Reutilization Authority, the land bank where many Urban Assets properties likely will wind up.

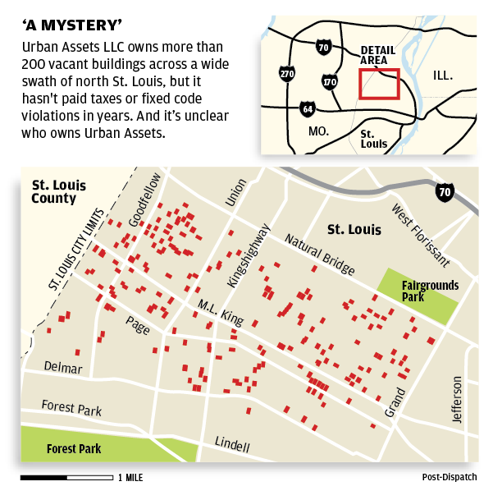

Noble filed paperwork to create the company in June 2008 and immediately started buying up cheap vacant houses at the city sheriff’s tax auctions. In about a year, Urban Assets amassed more than 240 parcels, stretched across a five-mile swath of the north side, from Grand Boulevard to the city line, between Delmar Boulevard and Natural Bridge Road. Most were houses, bought for just a few thousand dollars apiece. And they were mixed among occupied homes, empty lots and city-owned vacant structures — too spread out to make sense as any sort of larger development.

Since buying them, though, Urban Assets appears to have made no improvements to its properties. They’ve just sat there.

City property records show only one Urban Assets property has been sold to a new owner. Most, vacant to begin with, have continued to decay, and visits to several dozen of them in recent weeks shows a parade of board-ups, with broken windows, crumbling roofs and wild vegetation. People who have observed the houses say they’re rife with dumping, debris, sometimes drugs.

“I get a lot of complaints,” said Alderman Frank Williamson, whose 26th Ward north of Forest Park includes 19 buildings owned by Urban Assets. “And people seem to have a real hard time contacting them.”

Those complaints get turned over to the city’s Building Division, which has cited Urban Assets for countless code violations. But the company doesn’t respond, said Building Commissioner Frank Oswald. It doesn’t pay bills the city sends it to board up windows and mow grass either.

Between fines, fees, judgments and taxes, Urban Assets owes hundreds of thousands of dollars, city officials say. But with so many types of fines levied on so many buildings, the city can’t provide an exact total.

Eventually these properties wind up on the desk of Matt Moak, the city’s chief problem-properties attorney. It’s his job to sue or cajole the owners of derelict real estate into cleaning up their act, and in a city with more than 6,000 vacant buildings, Moak is a busy guy. But he says he’s never seen a case like Urban Assets. He’s filed lawsuits on many of their properties, but lawyers stopped showing up to defend them long ago. Now he’s preparing paperwork to put some of their buildings up for sale at a nuisance property auction in October in the hopes some new owner will buy them. There’s not much else he can do.

“It’s almost impossible for us to keep fighting them in court when they don’t show up,” he said. “I can’t go and arrest ‘Urban Assets.’”

AGENTS, INSIDERS

Complicating matters: No one knows who Urban Assets is.

Noble’s is the only name that appears on public documents associated with the company, and city real estate experts say he is likely a straw buyer. Missouri state law only requires that limited liability companies list a registered agent — not legal owners — so there’s no way to know for whom he’s buying.

Some real estate-watchers suspect McKee again. He took the same secret approach, and the same broker, to buy land for NorthSide. But McKee has denied involvement a number of times, including during 2009 testimony to the St. Louis Board of Aldermen, and no Urban Assets properties are located within his NorthSide project area.

Others suspect the Roberts brothers. North St. Louis-native businessmen Michael and Steve Roberts have bought and held real estate for years for a long-planned project near Kingshighway and Delmar — an area where Urban Assets owns a few parcels — and they have struggled to pay property taxes as their business empire has crumbled. Steve Roberts did not respond to a request for comment, but Michael Roberts recently told the Post-Dispatch that Urban Assets isn’t him.

“I’ve never heard of them,” he said. “If people think it’s us, I guess that’s some form of flattery. But it’s not us. We put our name on everything.”

Virvus Jones, the former city comptroller who used to work for the Roberts brothers, backs that up. He remembers Michael Roberts asking him to buy a piece of ground from Urban Assets, and talking with Noble about a deal.

“He never told me who his clients were,” Jones said. “It may just stay a mystery.”

For his part, Noble isn’t talking. Moak, the city’s attorney, said he’s asked Noble several times to reveal his client, to no avail. And the broker wouldn’t tell the Post-Dispatch either.

“I’ve got nothing to say to you,” he said last week to a reporter asking about Urban Assets’ ownership and the condition of its property. “I’ve been in north city for 50 years. There’s buildings that are collapsed a lot worse than that.”

Then Noble repeated that he would not name his client and abruptly walked away from the conversation. “I’m going to deny I’ve said any of this, by the way.”

His partner Goldman was only slightly more talkative. Confidentiality agreements, he said, prevented Eagle from naming its clients.

“������Ƶ wouldn’t appreciate it,” he said. Goldman did say he and Noble don’t own Urban Assets’ properties themselves. “We represent them, that’s all.”

And, he said, the client hasn’t paid them in years, not since they stopped buying land in 2009.

Eagle has other big clients though, including the city. For decades, the firm has held a contract to appraise property for the Land Reutilization Authority, the city-run “land bank” that takes over real estate that falls delinquent on taxes and doesn’t sell at auction. Eagle just received a three-year renewal in April; no one else bid on the job.

Every property entering LRA’s inventory — hundreds per year — gets a drive-by appraisal as part of the legal process of taking the real estate, said Otis Williams, executive director of the St. Louis Development Corp. Eagle gets $150 per house, plus other fees.

That adds up.

Since 2008, when Urban Assets started buying, Eagle has been paid $443,256 under these contracts, according to documents obtained through the Missouri Sunshine Act. That figure will grow thanks to the hundreds more parcels that have gone unsold at tax auctions this summer, including dozens belonging to Urban Assets.

Williams said he was not familiar with Urban Assets, but that Eagle has done a good job for the city.

“They’ve provided us with the services we pay them for,” he said.

When asked if the LRA contracts could provide leverage to get Eagle to pay fines or better maintain properties it holds for private clients, Williams said that was not something city officials had discussed.

“We have not looked at it that way,” he said. “We know Eagle is an acquisition agent for a number of developers. But we don’t normally look at that because our (LRA) process is distinct and separate.”

WHAT’S AT STAKE?

The whole situation highlights the struggle the city faces in maintaining its valuable, but too-often-vacant, century-old red-brick building stock, and of pushing owners to take care of their property without pushing so hard they walk away.

The issue flared earlier this summer when city officials ordered the demolition of the Cupples 7 Building, a historic but long-neglected warehouse downtown. That prompted conversations in City Hall about a building preservation fund or some other solution to mothball valuable structures. But similar scenarios play out everyday on a smaller scale in neighborhoods across St. Louis.

“The city needs to decide whether or not this is a priority,” said Andrew Weil, executive director of the Landmarks Association of St. Louis. “If they want to create the Wild West where people can flout code laws, that’s one thing. If they don’t, they have to allocate resources to deal with these buildings.”

Right now, the city’s strapped budget contains little money even to demolish dangerous vacant buildings it already owns, let alone to board up the ones it wants to keep standing. With private owners like Urban Assets, the best it can do is slap liens on a property, to collect if it’s sold.

In 2010, the city increased fees for vacant building owners, and it has taken a more aggressive tack in fining for code violations. That has helped pressure more building owners to either fix up or sell their property, said Oswald, the building commissioner.

But tracking down a responsible party can still be tough. A 2010 municipal law requiring vacant building owners to supply a phone number and address to the city is often ignored, Oswald said.

“How do you enforce it?” he said. “The good people do it, but the ones who are problematic just ignore it. It’s legislation that’s got no teeth.”

Meanwhile, many of these properties just sit there decaying.

‘IT’D BE A SHAME’

On a block of Enright Avenue, a bit north of the Central West End, there are fine old homes, many still well-maintained, with trim yards and flowers. And there’s a big empty Victorian, with a gaping window and small trees growing up the side. The shingles on the peaked roof are starting to crumble. It’s been owned by Urban Assets since 2008.

Shermond Palmer lives across the street. The house has been empty as long as he can remember, though at one point a few years back someone was working on it. Since then, though, it has just been fading away.

“It’d be a shame if it comes down,” he said. “They don’t make them like that anymore.”

The fate of the house on Enright, and most of the rest of Urban Assets’ property, may rest with the city. As the three-plus year clock on unpaid taxes ticks down, more and more are moving towards tax auctions. If they go unsold there, they’ll be added to LRA’s inventory of more than 10,000 properties.

That’s what happened Tuesday morning, in the gloomy lobby of the Civil Courts building downtown. About 150 people stood crowded in front of a sheriff’s deputy who read through a list put up for sale for delinquent taxes. Noble had a front-row seat, taking notes with an assistant. Goldman milled about in back, chatting.

It took more than an hour to get though the 420 properties. Some sold for asking price. A few bidding wars broke out. But most had no buyers. When the deputy got to the 17 owned by Urban Assets, no one bid on any, which means they’ll eventually be transferred to LRA, with an appraisal by Eagle Realty as part of the process.

The next auction is set for October. Urban Assets will have more properties on the block then.