JEFFERSON CITY — Last October, Kerri VanMeveren stood before a judge seeking answers that weren’t forthcoming.

A month earlier, the Cass County resident had filed a lawsuit against the , which regulates veterinarians. VanMeveren had complained about the care her horse, an 8-year-old purebred Arabian named Dennis, received from a local veterinarian. The board dismissed the complaint without an investigation.

Ignored by one arm of Missouri government, she sought accountability from another.

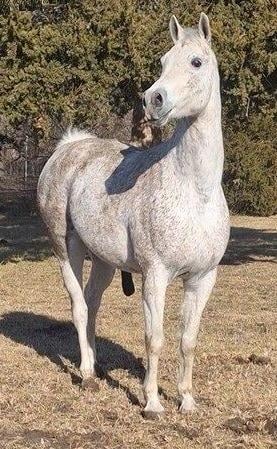

Kerri VanMeveren's horse, Dennis, grazes in his Cass County pasture. Photo provided.

VanMeveren was representing herself and, not being a lawyer, had questions about the court system. I was in the Cole County courthouse in Jefferson City that day waiting on another hearing. As often happens when people don’t have attorneys, VanMeveren had questions about procedure that the judge declined to answer. She asked Circuit Court Judge Christopher Limbaugh if he would record the hearing, which is common in contested cases. The judge said no. She asked if she could email her filings to the court. He said yes. In the end, the hearing was delayed.

People are also reading…

Earlier this year, VanMeveren got good news. St. Louis attorney Elad Gross agreed to take on the case. In July, Gross argued before Limbaugh that the case deserves to go to trial so VanMeveren can have her day in court. At issue is whether the Veterinary Medical Board is accountable to the citizens it’s supposed to serve.

“Why does this board exist in the first place if it doesn’t have to do its job?” Gross asks.

It’s a fair question.

VanMeveren’s issues began in February 2024 during Dennis’ treatment for a hoof issue. The prescription she needed was expensive, and she asked the vet if he would approve her buying it at a discount pharmacy — instead of from the veterinarian himself. He said no. She asked again. After some back and forth, the vet’s wife texted: “Just take your horse to someone else.”

VanMeveren was devastated. She tried to get Dennis another vet, but his condition deteriorated.

“I watched my horse suffer despite spending thousands of dollars with other vets and farriers who didn’t know how to help him,” she said. “At one point, his condition was so grim that I scheduled a euthanasia.”

She relented on that decision. Dennis is still alive, though he’ll never be a show horse.

When VanMeveren filed her complaint with the vet board, all she received was a one-sentence reply that said it chose not to investigate.

“I wasn’t just dismissed by the vet. I was dismissed by the system that’s supposed to hold professionals accountable,” VanMeveren said.

So she filed a petition with the Cole County Circuit Court, seeking a declaration that the board was at least required to conduct an investigation.

The board’s attorneys say that’s not what the law requires. In fact, they say, the board has discretion not to investigate and the law only requires the one-sentence reply VanMeveren received.

“The plain language of the statue is clear, and nothing more is required,” they wrote in a motion seeking a ruling in the board’s favor.

There have long been questions about the various Missouri boards that regulate professionals, like doctors, nurses, lawyers, teachers and veterinarians. Most of the regulatory boards operate under a veil of secrecy. The veterinary board, for instance, says the results of its investigations are confidential. Last year, there were 16 veterinarians disciplined among 74 complaints that were filed. What happened to those veterinarians is a secret.

That’s why VanMeveren’s lawsuit is worth taking to trial, Gross said.

“The central issue is protection of Missourians who are expecting professional service from people who are regulated,” he said.

Having talked to animal-rights activists around the state, VanMeveren is sure she isn’t alone. Her complaint didn’t get the result she wanted, but she’d like to know that the vet board will at least investigate legitimate complaints and show its work in some capacity.

Indeed, Bob Baker, executive director of the , said the vet board has long been a concern for his organization. That’s in part because four of the six members are chosen by a veterinary association, creating an incentive to protect veterinarians rather than police them. The veterinary board operates with less state oversight than any other medical board in the state, Baker says.

“There are countless people like me who have filed complaints — real, documented, evidence-backed complaints — only to be ignored,” VanMeveren said. “The Missouri Veterinary Board is a taxpayer-funded body. But it acts like a shadow government — opaque, insular, and unaccountable.”

Some day soon, Limbaugh will rule on whether VanMeveren can have something in a courtroom that the veterinary board never gave her: the right to be heard.

Post-Dispatch photographers capture tens of thousands of images every year. See some of their best work that was either taken in June 2025 in this video. Edited by Jenna Jones.