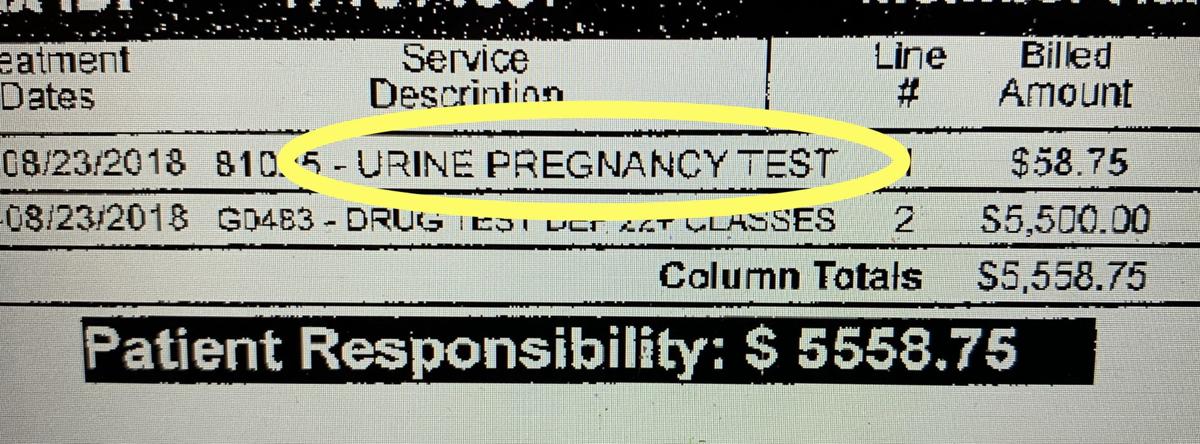

Two things about the medical bill the St. Peters resident received in the mail stood out.

The first was the cost.

One of the two items on the bill was a drug test. It cost $5,500. She thought that seemed high.

The second item on the bill seemed out of place.

It was a pregnancy test.

The bill was for her son.

The woman maintains insurance for her grown son. She asked that I not name her to protect her son’s privacy. He has battled addiction, and at the time she received the bill, he was under the care of a man named Marvin Shelton.

Shelton owns a series of homes in the St. Louis region that he claims to operate as halfway houses for some of the most vulnerable members of society. Under the umbrella of a nonprofit he started, called The Community Counseling & Housing Services, Shelton and his chief operating officer, Stacey Smith, take in veterans, people leaving federal prison, people with mental health illnesses and addictions. They promise a sober home, various services and have historically gotten referrals for their tenants from local hospitals and other social service agencies.

People are also reading…

In the past three months, a growing list of folks who have lived at the homes tell me they are poorly run, often don’t have working heat or water, and that Shelton and Smith provide none of the services they promise when recruiting people to live there.

“It’s a scam,” the woman from St. Peters told me. “They are preying on people.”

Her son was referred to Shelton while he was a patient at Southeast Missouri Behavioral Health, a rehab facility in Farmington. One of the things Shelton does when recruiting people to live in his homes, according to his , and the people who have lived there, is require them to provide their medical insurance card, either Medicaid or Medicare.

That’s why the medical bill caught this woman’s attention. It came in August 2018, shortly after her son had moved into one of Shelton’s homes on Eagle Drive in Hanley Hills. The date of the phantom pregnancy test and the $5,500 worth of drug tests was the day after he had moved into the house.

Like the St. Peters mother, the insurance company eventually realized something was askew. She never paid the bill, and she doesn’t think the company did, either.

But after she read my columns about issues with Shelton’s homes, she wondered: Is this how he’s making his money, beyond charging $500 a month rent from people and often not providing them a working furnace?

Shelton didn’t return numerous calls for this column.

“He talked a good talk,” the woman said of Shelton, during the time he was recruiting her son to live there. “������Ƶ were going to do so much to help him. But they did nothing.”

Within a few weeks, she says, her son relapsed. He went to another rehab facility, and now, she says, “he is finally doing better.”

She’s grateful her son wasn’t in Shelton’s care for long.

So is another St. Louis mother, whose grown daughter ended up at Shelton’s home on Beacon Avenue in the Walnut Park neighborhood. That’s the first of Shelton’s homes that I visited, last December. On the day that I was there, the heat was off. There was next to no furniture in the house. An extension cord running from next door provided electricity.

Conditions weren’t much different a year earlier, when the St. Louis mother — she also asked that I not use her name — did a spot check to see how her daughter was doing.

“Her living space is unacceptable,” she later wrote to her daughter’s social worker, at Mental Health America, which was paying her rent. “There were no couches, chairs or lamps in the home. They do not have a dinette set to eat meals.”

Her daughter’s room was in the attic. She had no closet.

Needless to say, the mother worked with social workers to find her daughter a new place to live. One by one, various social service agencies in the St. Louis region are reaching the same conclusion: No more referrals to Shelton’s homes.