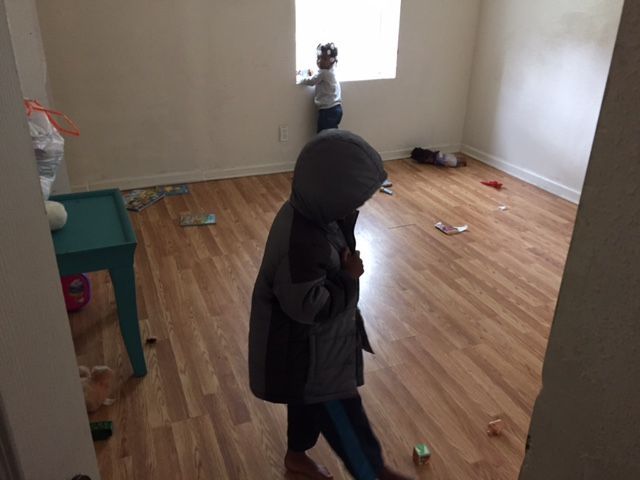

Aaliyah Dinwiddie props her elbows on the empty windowsill in her room and stares into the abyss.

The 2-year-old is barefoot and in jeans and a white top. Some books are strewn about the floor of the bedroom she shares with her brother, Rashaud, who is 5. “If I Ran the Rain Forest,” is there, and, of course, the Dr. Seuss classic, “Green Eggs and Ham.”

A set of rickety shelves holds some toys and clothes. There are no beds. No chairs. No blankets.

The two children sleep in the front bedroom with their parents — Shaun Dinwiddie and Erica Marshall — on two twin beds, in this “new” apartment on Ashland Avenue in the city’s poverty-ridden 4th Ward.

Until December of last year, the family lived across the street.

Pointing out the front window at their former apartment, Dinwiddie explains the change of location.

People are also reading…

“See that green paint around the windows?” he asked. “That covers up where the kids got lead poisoning.”

In November, both children were tested for lead exposure. Rashaud’s number, 4 of lead per deciliter of blood, was high. But Aaliyah’s was put-her-in-the-hospital-immediately high, a count of 60. in 2014 recorded such a high level of lead in their blood, according to state records. The level of lead requiring intervention is 5 micrograms of lead per deciliter of blood.

Seeing her at the windowsill is a chance moment that frames her story.

A few months ago, when she was just a little bit shorter, and struggling to toddle around, she put her fingers on the chipping, lead-based paint on the frame of a window across the street. She pulled herself up, for days or weeks. Maybe she dreamed of what life might be like outside the prison of poverty. Perhaps she saw a rain forest in the trees, or castles in the boarded-up homes across the street. At 2, with lead poisoning at such a high level, and stuck in generational poverty, much of the script of her life is already written.

Lead poisoning “is insidious,” says of Washington University. She’s an associate professor of emergency medicine who specializes in toxicology. Too often, children ingest lead dust or chipped lead-based paint, and the symptoms of the potential life-altering effects of lead poisoning are slow to show up. “Sixty is high,” she says, but if caught early enough, long-term effects aren’t guaranteed.

Aaliyah now takes 100 mg of Chemet daily, a drug that seeks to cleanse the blood of lead. The pills are large and hard to swallow and have a pungent odor. Getting her daughter to take them every day isn’t easy, Marshall says.

Her speech and comprehension seems behind, offers her father. “It’s dangerous,” Dinwiddie says. “We’re going to have to deal with this for the rest of her life.”

He should know. As a child growing up in the Greater Ville neighborhood, Dinwiddie, now 27, had lead poisoning. So did his brother, Juron. The boys were in and out of foster care programs. In second grade, while in the Lindbergh schools as part of the city’s desegregation program, Dinwiddie met an angel.

Susan Burney was his teacher. She and her husband, John, who both retired from teaching in 2009, sought to help the boys. They acted as resource foster parents, taking the boys in on some weekends and holidays, helping to provide some stability in life.

“Once I had gained Shaun’s trust, I knew he was going to need adults in his life that could provide consistency, help instill values, and love him,” Burney says.

The couple continue to help the family when they can. ������Ƶ were there when Marshall went into labor with Rashaud. They helped them get the electricity turned back on this month.

But even with such help, the family barely makes it.

“I’ve had good jobs,” Marshall says. “But when you’re a mother, it’s harder. Everything changes. It’s either transportation or child care. It’s the smallest things that are hindering me.”

Dinwiddie is disabled because of epilepsy. His monthly disability check of $733 pays the rent but not much else. Marshall and the kids get about $500 a month in food stamps. She had a job at Family Dollar, but the company switched her to a location farther away and she couldn’t arrange transportation and child care. Dinwiddie can watch the kids sometimes, but it’s not ideal with his occasional seizures. They have a car but no insurance.

They don’t want to live on Ashland Avenue, but they also don’t feel like they have any other options.

This is life on much of of St. Louis, where generations of children nibble at lead-paint chips and not enough is done to prevent it.

Eventually, the medicine will cleanse the lead from Aaliyah’s blood.

She’ll be left with her window, and her imagination, wondering what life might be like on the other side.